Agnieszka Pilat: "ROBOTa"

MODERNISM GALLERY

724 Ellis Street, San Francisco

November 3 - December 21

Opening reception November 3, 6-8pm

As a dedicated young draughtsman with an interest in painting, Leonardo da Vinci was taken by his father to a Florentine master named Andrea del Verrocchio. Impressed by the young man’s talent, Andrea apprenticed him, providing Leonardo with training in skills underlying the masterpieces for which he’s now famous. Leonardo also had a hand in Andrea’s own paintings, contributing to altarpieces and private commissions. Recognizing the value of apprenticeship for artists of promise, the painter Agnieszka Pilat recently offered apprenticeships to Digit and Spot. Unlike Leonardo, Digit and Spot are robots. Products of Boston Dynamics, they’re widely admired for their mechanical dexterity. But it took Pilat – who was schooled in the European tradition of figurative painting – to appreciate their latent creative potential. Modernism Gallery is pleased to present the results of this unprecedented year-long apprenticeship: a dozen large-scale oil paintings that offer visual delight while expanding upon the conceptual groundwork of Marcel Duchamp and Jean Tinguely by questioning conventional ideas about creativity, authorship, and even human nature. “Working in close contact with a robot gives the impression of an encounter with another mind,” says Pilat. “It seems that the robot has agency.”

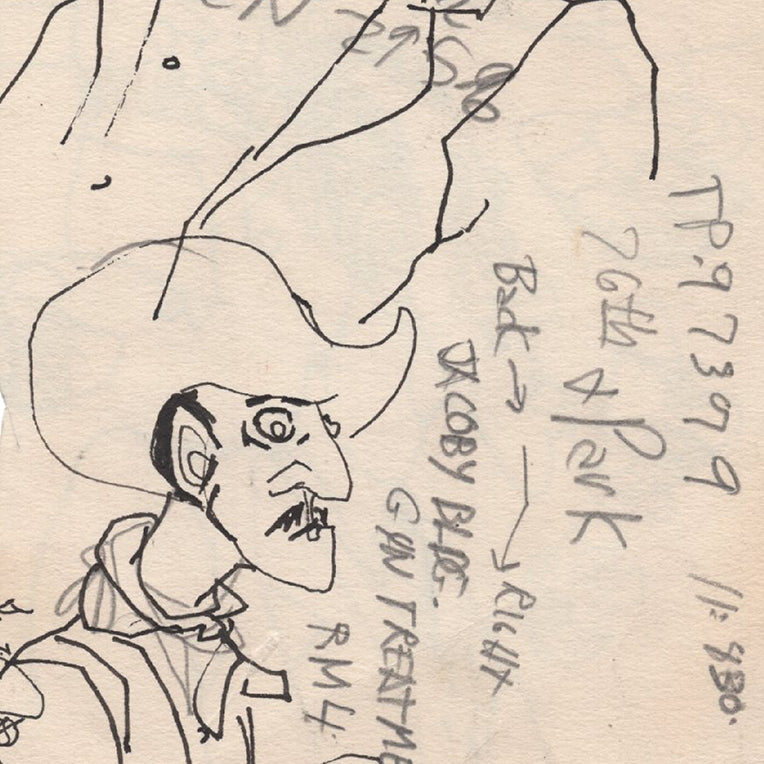

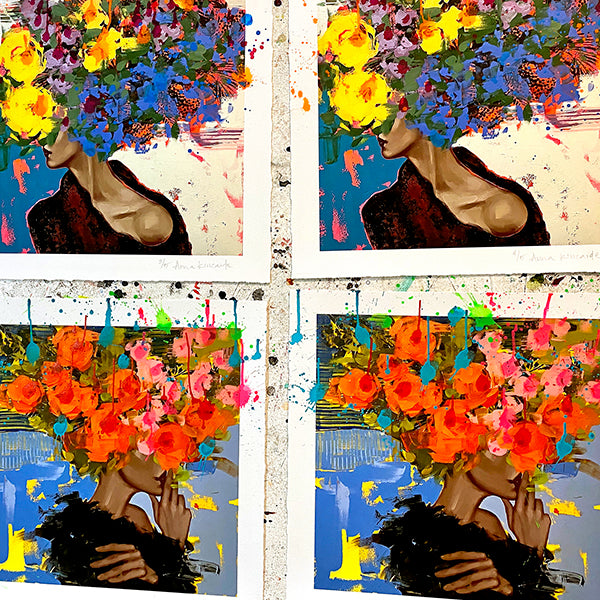

Each of the two robots shows a distinctive artistic personality. With a humanoid form and movements that must be programmed in advance, Digit manipulates brushes with an energetic angularity reminiscent of Jean-Michel Basquiat, as can be witnessed in a video on view at Modernism. Shaped like a dog, Spot holds paint sticks in his mouth while making controlled motions under Pilat’s direct guidance. As can be seen on the gallery walls, the paintings have calligraphic qualities evocative of Cy Twombly. Spot has also specialized in making multi-colored circles of spattered paint tracked with his feet, several of which are on view at the Modernism show. The circles are geometrically perfect yet spontaneous in their color patterns, a sort of hybrid of Hard-Edge Abstraction and Abstract Expressionism.

Pilat was first acquainted with Spot and another Boston Dynamics robot named Atlas when they modeled for her several years ago, reenacting some of the most important works in art history for her previous Modernism exhibit. But this new body of work provides a manifestly different perspective, one that comes from within.

“All of my apprentices’ gestures are inspired by their motor control, and also reveal their mechanical limitations,” observes Pilat. “Both Digit and Spot are imperfect extensions of my arms. When they transfer my aesthetic ideas onto canvas, those ideas are translated into the physical language of machines.”

Pilat finds the awkwardness of the translation to be edifying. “Through flawed execution, my mastery of painterly tradition is reinvigorated,” she says, expressing concern about the decorative superficiality she sees in most contemporary painting. “I am the robots’ master, and also their apprentice.”

In the spirit of apprenticeship, Pilat is careful not to take all of the credit. “Imperfections make robot art strangely original,” she observes. The reality of robotics is far less impressive than the hype – no risk of Spot overshadowing her as Leonardo did Andrea del Verrocchio – and this paradoxically this makes them more impressive.

“The threat to human artists and their exhausted abstract gesticulations is to be found in the machines’ mistakes,” Pilat asserts. “Through their errors, robots promise to make art interesting again – interesting for people and perhaps one day for their fellow machines.”

Artist statement:

In the 15th Century, mastery was well defined. The art of painting was clearly delineated. Today, painting is exhausted. Abstraction is decorative. I have taken apprentices in order to teach the next generation – to experimentally code what robots may someday be able to do on their own – and also to learn how to paint anew. I am the robots’ master, and also their apprentice.

Apprenticeship begins by introducing each of my students to traditional painting implements and materials. Holding a brush or an oil stick, the robot is guided through gestures that I improvise or program in advance. These gestures are inspired by my students’ motor control, and also reveal their mechanical limitations. Digit and Spot are imperfect extensions of my arms. When they transfer my aesthetic ideas onto canvas, those ideas are translated into the physical language of machines. The awkwardness of the translation is edifying. Through flawed execution, my mastery of painterly tradition is reinvigorated.

Working in close contact with a robot gives the impression of an encounter with another mind; it seems that the robot has agency. This experience contradicts expectations about machines operating reliably and predictably. When a robot fails at a task repeatedly, a human observer may even feel a pang of empathy. That has been my experience with Digit and Spot. Paradoxically, they have taught me about humanity.

Bringing robots into my studio, I expected to grapple with art history on a conceptual level. Even before Walter Benjamin published “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in 1935, artists sought to reimagine painting in relation to the machine, to find a new purpose for oil on canvas. I assumed that making art with robots would bring new insight to old ideas about originality, creativity, and the artist’s hand. What I have discovered through practical experience is more profound, and the material evidence of that discovery permeates the art made with my apprentices.

Imperfections make robot art strangely original. The threat to human artists and their exhausted abstract gesticulations is to be found in the machines’ mistakes. Through their errors, robots promise to make art interesting again – interesting for people and perhaps one day for their fellow machines.