Al Diaz and Jean-Michel Basquiat rewrote the rules of street art before taking different paths: one as a hard-grafting musician, the other as an iconic artist. Both would be ravaged by drugs. Four decades on, the story is far from finished.

When Al Diaz showed up at the premiere of Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child, a documentary about his old friend, it should’ve been a point of pride.

The graffiti they developed together in 1970s New York City was now being celebrated as pioneering street art. But when Al saw a picture of himself at the event, he looked like shit. There was no hiding the signs of heroin. That the film lamented Jean-Michel’s death from an overdose at 27 only made it worse.

“Addicts don’t learn from other people’s mistakes,” Al says now. “You can tell me a thousand times that the flame is hot but until I stick my hand in the fire, I won’t believe you. It’s what I have done throughout my entire life – but that was the moment I decided to change.”

Al had been writing graffiti since the age of 12 as ‘Bomb-One’. Back then, it was all about plastering your name and number across the city – a pissing contest that, for Al, felt increasingly pedestrian. So at 16, he and schoolmate Jean-Michel Basquiat – a precocious kid who came from a broken home in Brooklyn – aspired to something more meaningful than scribbles.

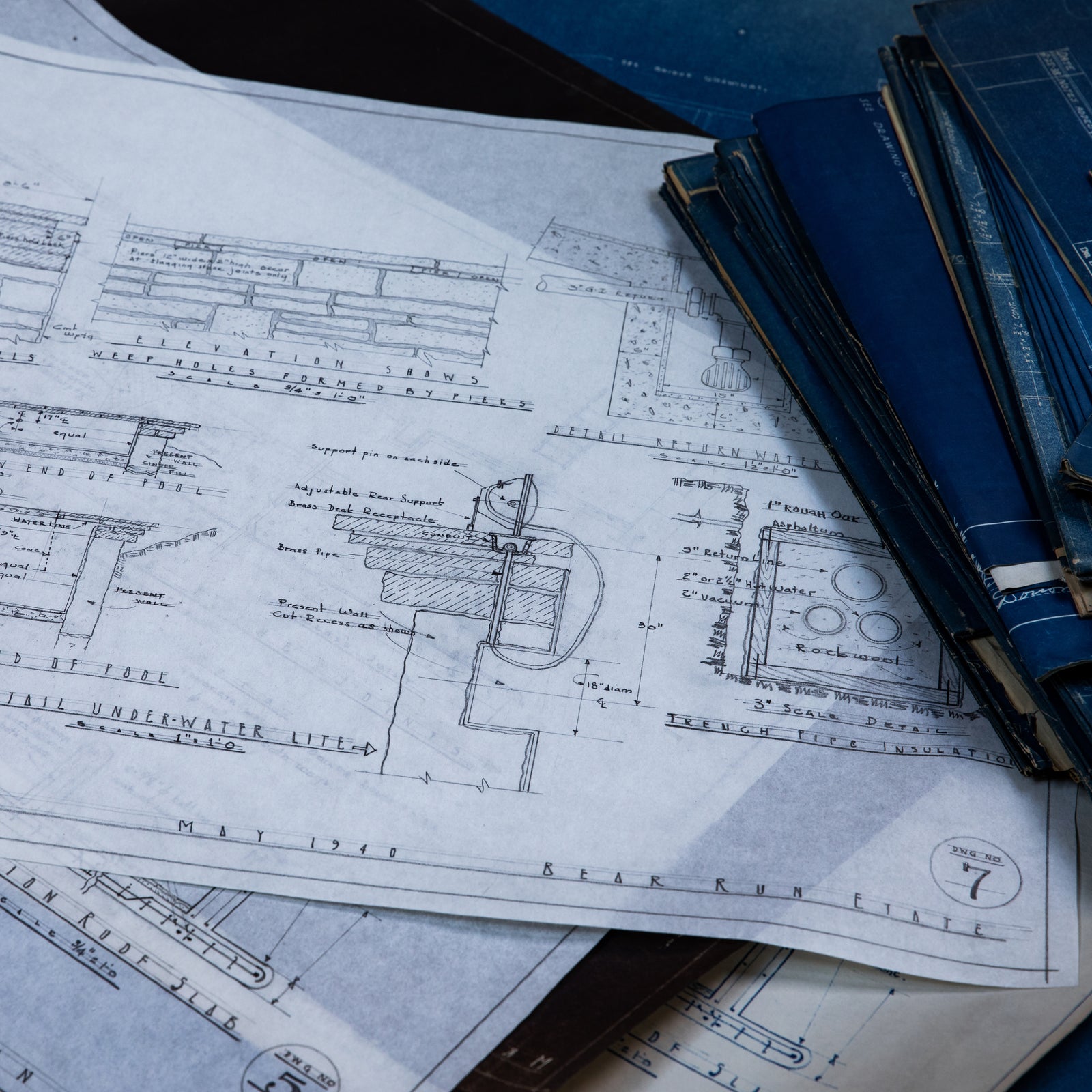

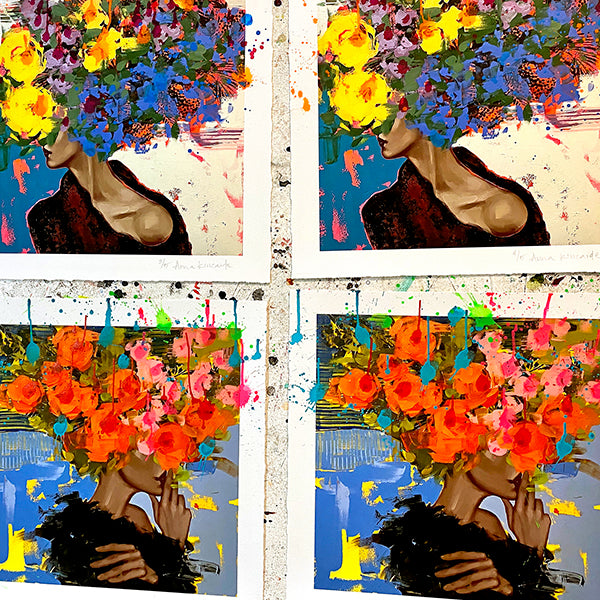

Jean-Michel Basquiat and Al Diaz, previously unpublished – one of only a few known images of the infamous duo together. Courtesy of House of Roulx.

Operating under the name SAMO© (pronounced ‘same-oh’), the pair sprayed oblique poetry all over Manhattan’s Lower East Side – channeling their frustration with society through satirical advertising slogans. (One read: “SAMO© as an end to mindwash religion, nowhere politics and bogus philosophy.”)

“We were doing something completely new to graffiti culture, but not to the planet,” says Al. “To us it wasn’t so different from people writing political statements on the walls of ancient Rome.”

By the time the duo turned 19, though, their goals diverged. Al grew interested in making music, preferring to stay low-key; Jean-Michel wanted to blossom into a famous artist. “We had been like brothers for years and just started to get on each other’s nerves, the way teenagers do,” he says.

Jean-Michel had a magnetic quality, Al says, and he was shrewd about using that to his benefit. Seeing him swept into Andy Warhol’s circle, lauded by the art world, came as no surprise.

But Al knew that Jean-Michel would’ve been uncomfortable fitting into a lifestyle he used to mock. “Some of the shit he had to do in order to be successful caused a lot of internal conflict,” says Al.

“It made him much more angry, defensive and distrusting of others. I believe a lot of that contributed to his ruin. It manifested itself in his appetite to numb himself, to always be high.”

Al, meanwhile, had to deal with some issues of his own. In 1987, a drug dealer attacked him with a baseball bat, breaking his jaw and knocking his teeth out.

“I cried after seeing myself in the mirror; I looked like a monster,” he says. “When you get assaulted to the point of being in intensive care, that shit poisons you. It just led me to using heavier and heavier drugs.”

By 1996, Al had to retreat to Puerto Rico, where his parents are from, in search of stability. He built a house, studied electricity and gradually eked out a healthier existence. Still, it was only ever going to be an extended break. “Few places can stimulate you like New York,” says Al. “It felt like I couldn’t get on with my life until I returned.”

In 2000, a year after coming home clean, Al found a bag of heroin on the street. It sent him straight back into a spiral of addiction that lasted 10 years. Seeing himself at the opening of The Radiant Child proved a turning point, but when his flatmate said, “They’re never going to make a movie about you,” it gave him added motivation.

Emerging from rehab in 2011, Al gathered up a pile of ‘wet paint’ signs he’d found scattered across the NYC subway system. Something about their design inspired him to cut them up like ransom notes, rearranging the letters into pointed messages that he’d then re-hang on subway walls. It felt like a creative rebirth: Bomb-One was back.

“But when Trump became president, I was so disappointed with America that I couldn’t really express that with such a limited vocabulary,” he says. “There was a sense of: ‘Jesus, is this the status of mankind?’ It felt like time to bring back SAMO©.”

With the benefit of maturity, Al is better equipped to finish what he and Jean-Michel started: returning to the same streets, grappling with the same issues, only more eloquently.

It’s hard to know how things would’ve turned out had his old collaborator lived, but the pair did have the chance to work together on some projects in the mid-80s. The year before Jean-Michel died, in 1986, he even gifted Al with a painting titled ‘From SAMO to SAMO’.

Speaking to the 58-year-old now – sitting topless in a sweltering New York bedroom, a black cat lounging on the sofa behind him – he seems remarkably composed for all the shit he’s been through.

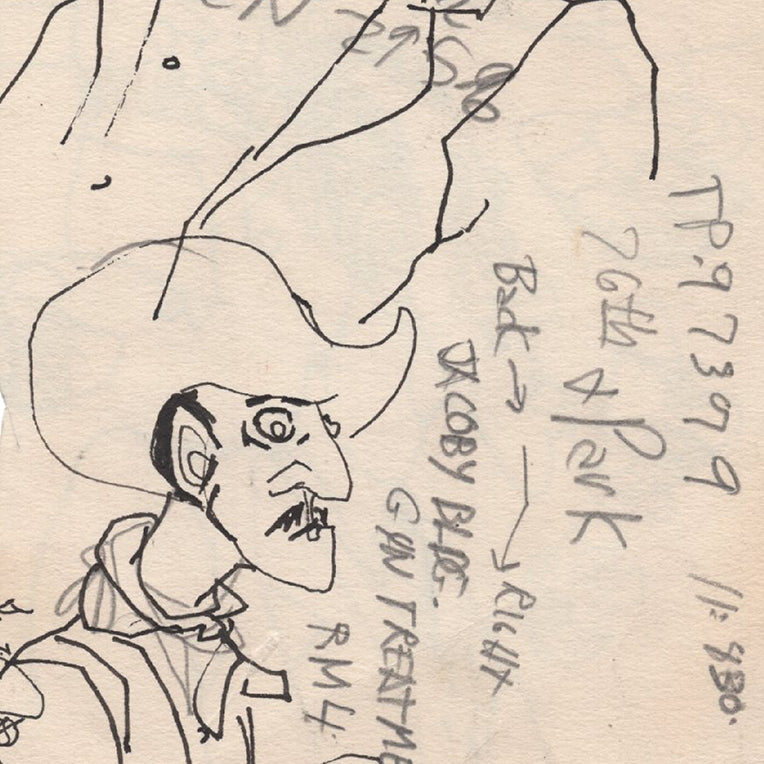

Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1976. Photo by Al Diaz. Courtesy of House of Roulx.

But if there’s one thing that still nags at him, it’s that he sold Jean-Michel’s painting to buy a four-track recorder soon after he received it. (In May, a Basquiat painting sold at auction for over $110m, setting a new record for a US artist.) Over time, though, Al’s learned to be cool with it.

“You have to be,” he says, laughing. “Whatever I’ve done in the past was essential for me to be where I am now. So the hypothetical question of, ‘Would you do anything different?’ is kind of a moot point. We are the sum of our experience.”

Follow @samocopyrightdotdotdot on Instagram or visit House of Roulx.

This article appears in Huck 61 – The No Regrets Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.